Post-FOKI

Posted: December 10, 2011 Filed under: Uncategorized 1 Comment(I have grayed out most of my original post; I have only left the goals in black. My post-FOKI is in green.)

Introduction

In my eighth grade English class, Mrs. Koval assigned the young adult (YA) novel Homecoming by Cynthia Voigt. I had read it a year or two before, so Mrs. Koval decided that I could read the next novel in the series, Dicey’s Song. She sent me to the library to check it out. That was on a Friday. The next Monday, I informed her that I had finished the book and asked what my next step was. She was visibly frazzled. I believe her words were, “Well, Ashley, I had really expected you to read it chapter-by-chapter along with the rest of the class.” (At the time, I thought she was angry with me, though now looking back through a teacher’s eyes, I realize she simply didn’t know what to do with me then.) This story, for better or worse, exemplifies my relationship with reading through my young adult years. I was a marathon reader, reading for hours at a time without stopping, but I never reflected on what I was reading. As I said in my Journey Book reflection, it wasn’t until my later teen years that I was personally affected by literature at all.

That experience (or lack of experience, really), is why I am really excited to take this class. I get to learn about a genre that I never really got to know. This is also the first course I have taken in the CED (thus my blog title), and I am excited to explore the world of teaching young adult literature and, more generally, the academic world of education.

My Three Selves

Professional Self

My undergraduate degree is in English and Psychology from West Virginia University, and my Master’s degree is in English Linguistics from North Carolina State University. Though both of my degrees say “English”, that’s only because linguistics is often housed English departments (literary analysis has never been my strong suit, unfortunately). My interest and background in linguistics, specifically sociolinguistics (a field few have heard of, so here is Wikipedia’s overview), has a strong social justice component. I know that every person speaks a dialect, that every dialect is rule-governed and complete, and that there simply are no inferior dialects or languages; these are facts, but unfortunately, they are not well known facts. Given that dialects are the “last back door to discrimination” (Lippi-Green 1997:73), I am obligated to pass the knowledge I have along.

I learned as a Teaching Assistant at NCSU that I also love teaching, and I have been teaching composition here since I graduated. My knowledge of how language works translates nicely into the composition classroom. The class I teach focuses on the different academic disciplines, rhetoric, and academic argumentation, rather than literature. I have no experience in teaching literature or in Curriculum and Instruction, nor do I have any K-12 experience.

Literate Self

I don’t remember reading much YA literature as a young adult. I read so much so often (as it was my only source of entertainment, since we didn’t have television and I lived on a farm with no neighborhood children to play with), so I moved quickly to reading adult novels. They simply lasted longer. I do remember some things, like the Homecoming series I talked about above, but I also remember reading my father’s Sidney Sheldon novels in elementary school. YA literature simply didn’t figure largely in the development of my literate self.

I do have some adult experience with YA literature. My brother, who is six years my junior and has a different set of talents and interests than I do, read much more YA literature than I ever did. I served as his tutor in middle and high schools, so I read his assigned books along with him. I also took a YA literature course in college, and while most of it has left me now, I remember some of the foundational ideas.

Virtual Self

My husband claims I am an internet addict, but really, until recently, I was most definitely an online spectator, not a participant. I even refused to join Facebook until a year ago! Now, however, I have a personal blog (where I keep my distant family updated on our household; the past two months have been extraordinarily busy, so that has fallen by the wayside temporarily), I have joined Facebook, and I participate in several online communities (e.g., Pinterest, a virtual bulletin board to keep track of creative inspiration of all sorts).

I also have a virtual teacher self. I teach a “Bring Your Own Computer” English 101 class at NCSU; my students are required to bring a laptop to class each day. They turn in all assignments online (I use Moodle), and I give them feedback electronically. More recently, now that all students have a Gmail account, I have started using Google Docs and other Google Apps for classroom activities, and I am available on Google’s chat feature for student support.

Goals

Professional

I definitely look forward to learning what teaching a literature-based course means. I have taken them at the college and graduate level, of course, and I know most of my high school courses were lit-based, but I am ignorant of the pedagogy surrounding that type of class. Given my lack of personal connection to YA literature as a young adult myself, I would like to learn how to facilitate that connection for other young adults. I feel like I missed out on good experiences, both personally and socially, by not connecting with the literature I was reading, and I don’t want my future students to miss out as well.

Wow! Yeah, I definitely learned a lot about YA lit – both how complex it is as a category of writing, and also how complex it can be to incorporate it into the classroom. While I don’t know that I am confident that I will always be able to pick the perfect work,, I definitely feel much more prepared.

As for teaching a lit-based course, the Waves of Change Voicethreads really helped me understand the breadth of pedagogical theories that are out there. That assignment really gave me a good basis for understanding the lay of the land, and I look forward to diving into individual theories later on, and using that assignment as a basis for understanding how they fit in.

Literate

I definitely look forward to reading and connecting with some YA literature. The better I can learn to do so, the better I can teach my students to do the same.

And read YA literature I did! Seven books (Rot & Ruin, Dust & Decay, Please Ignore Vera Dietz, The Girl who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of her own Making, Feed, The Glass Castle, Fun Home). I have to admit, it didn’t feel like work. I enjoyed each of them, and I feel like they have me a good understanding of what YA lit can offer young adults and the different ways it can be used in the classroom.

Virtual

Already, I can tell that my assessment of my virtual teacher self as adept and cutting edge was … generous (if not just outright wrong). I am generally comfortable tackling new technologies, I just rarely do so unless I have a reason, so I look forward to learning and becoming literate in the various technologies we will use for this course. I especially look forward to thinking about how they can be applied to my current classroom setting (college composition) as well as potential future settings, specifically, secondary English classrooms.

I am definitely, definitely more confident in this area. I’m already thinking of using Twitter next semester to field questions from students (though Meg uses Facebook groups, which is almost equally appealing, so I’m trying to decide between the two). I like WallWisher for questions; I have my students run most discussions in my classroom, so this would be a good tool for me to introduce to them. And I’m sure that VoiceThread and some of the bookmarking sites will make their way into my classroom eventually. I really like all the tools we have used, but I don’t want to overwhelm myself (or my students) by introducing them all at once.

I also look forward to learning how to teach some of these different technologies. I have learned the hard way in my English 101 computer classroom that, while students today are digital natives, that doesn’t necessarily mean that they are fluent in every dialect – for example, I have watched students exchange Twitter names (handles? identities? see, I’m still learning too) on the first day of class, and then not know how to attach a document to an email. It’s a big digital world out there, and I want to be able to help students work towards a greater digital literacy.

Here’s what I learned here: What’s cool about using Facebook or Twitter is that these are the technologies that most students already know how to learn. Basically, I’ve noticed that the web-based programs are the ones most students are comfortable with, so those are the easiest to integrate into the classroom. The more social-networky it is, the more likely it seems that students can pick up on it. Now if I could just get them to see that Word is almost as intuitive …

Overall, this has been an awesome semester. I’ve learned so much about YA lit and about technology (and the links between the two!). This has been a wonderful first excursion into the education community, and I feel prepared – and excited! – to continue my journey.

Synthesis and Reflection

Before I wrote my Journey Book reflection or this inventory, I never really thought what kind of personal impact literature had on my life. I had always taken for granted that I was a reader, and that reading was a large part in my child- and young-adulthood. It wasn’t until I was challenged to come up with a piece of literature that stuck with me that I realized that wasn’t necessarily the role reading played in my life. I would like to at least try to give students a different experience than I had. I think literature, and especially YA literature, can be an asset for young adults who are just learning who they are.

While thinking about and writing my professional inventory and goals, I also realized that if I want my current teaching experience at the college level to translate into teaching at the secondary school level, I need to work to find the connections. I am already beginning to see that it is a different dialect of education than I speak … if not a whole different language.

Works Cited

Lippi-Green, R. (1997). English with an Accent: Language, Ideology, and Discrimination in the United States. New York: Routledge.

A Radical Change Proposal for NCSU’s Common Reading Program – My ALP

Posted: December 9, 2011 Filed under: ALP, Bookhenge 2 CommentsI began my ALP with the intention of getting some student feedback on NCSU’s Common Reading Program (CRP), and using that feedback and my other research to make some suggestions for the program. I wasn’t sure what form those suggestions would take, I simply had a notion that the program wasn’t functioning at its full potential and wanted to explore some options.

So the first thing I did was distribute a survey to my students (I used Survey Monkey) that asked some basic questions about what the common reading was used for and asked for their thoughts about it. Most of the students’ critiques of the CRP at State simply confirmed what I already knew: that the program was problematic and often left students confused or frustrated. It was good to finally get some official responses from them, though, which served as a jumping-off point for the rest of my project.

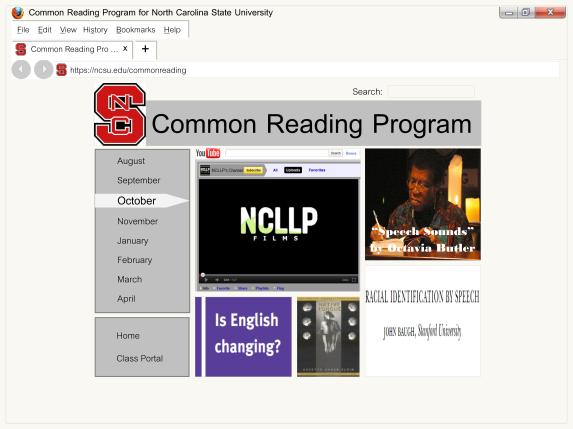

Once I read the article on the CRP at Buffalo State College – they use a multimedia CD with different readings – I knew that was the direction I wanted to take my proposal, and the interactive website idea was born. I had fun curating the materials and platform for my proposed theme and month’s unit – the overall theme would be “Broader Horizons,” and this individual month’s unit would be “Language” (of course). Each of the five resources, shown in the mock-up below, are related to our understanding of and ideas about language, with some social justice components thrown in for good measure. Each of the resources is explained briefly in the video.

Where this project goes from here, I’m not sure. While I think the current program is problematic in some ways, it works well for some students (and some colleges within NCSU), and there are a lot of really dedicated, well-intentioned people in charge of the program. This ALP certainly isn’t a critique on them, but rather on some of the unintended effects the program seems to have. While my suggestion would be a radical change, I think there are much smaller steps that could be taken to make the current program work better. That being said, however, I think considering shifts away from the standard can only benefit programs like the CRP, and that was my goal with this project.

Without further ado, then – my ALP!

_Dust & Decay_ Book Review

Posted: November 29, 2011 Filed under: Bookhenge Leave a commentDust & Decay is the second book in what will be at least a three-book series by Jonathan Maberry. The novel takes place in zombie-filled, post-apocalyptic America, and follows the adventures Benny Imura, his brother Tom, his girlfriend Nix and their friends. The group has decided to leave Mountainside, their small community that refuses to look past their meager surroundings towards a better future. Benny’s group wants to build a better future, and so they need to move on. Their goal is to travel east through the Ruin to find the origin of the jet plane they saw at the end of Rot & Ruin. Of course, not all goes as planned, and on their journey, they run into some dangerous and disturbing obstacles: zombies who are stronger and faster than any seen before, dead men who did not reanimate as zombies, and the mysterious Preacher Jack. While going east is a way for all of them to escape their past, Benny and his friends discover that there is still some unfinished business for them close to home.

What I liked most about this novel was Benny. My only complaint about Rot & Ruin (which I loved!) was that Benny’s attitude towards Tom changed too slowly. In this novel, there is none of that. While Benny is still clearly a teenager (his banter with his friend Choang and his relationship drama is testament to that), he has grown more mature and understanding, and was easier for me to read and relate to. He even challenges Tom’s decision to abandon his post as unofficial sheriff of the Ruin, which is a sign that he really has grown out of his self-absorption. I enjoyed following him in this novel, and I look forward to seeing how he grows in the future.

The other characters have developed as well. Lilah, who had been severely isolated for years, comes out of her shell a bit and I would argue that Choang has the strongest character arc in the novel. Maberry does a wonderful job of creating rich, full characters that endear you to them and make you cheer them on. The more I get to know these kids, the more I want to know.

If I had to name any gripe I had about the novel, it would be that it clearly is set up to have a sequel. There are several unanswered questions, and clearly some unaccomplished goals at the end of Dust & Decay. But really, I’m only complaining because the book left me wanting more – I can’t wait for Flesh & Bone!

Dust & Decay is another captivating novel by Jonathan Maberry. It was published in 2011 by Simon & Schuster (ISBN 978-1-4424-0235-0). It is available through their website for $17.99.

_Rot & Ruin_ Book Review

Posted: November 28, 2011 Filed under: Bookhenge Leave a commentFifteen-year-old Benny Imura has to find a job. He lives in Morningside, a small community somewhere in what used to be California, and when residents turn 15, they must find a job or have their food rations cut. Benny finds that he doesn’t find any job in town to be worth the time or money, so he reluctantly joins his brother Tom’s business. Tom is a respected zombie hunter in town, though Benny is much more impressed with two other local hunters, Charlie and Hammer. He thinks of his brother as a coward, and believes that Charlie and Hammer are tough and strong and, well, cool. Morningside is, in some ways, a fortress, designed to keep zombies outside in what is called the Big Rot and Ruin. In Benny’s world, all the dead “reanimate” into zombies and become mindless beings only incited to eat when they are alerted to someone living. Benny’s first trip out to the Ruin with his brother begins to change his ideas about the world, and that change continues throughout the novel. Benny learns that the real villains aren’t the mindless zombies (they used to be people, after all, and they have no intent to harm), but rather still-living people who choose to prey on other survivors.

Author Jonathan Maberry uses a few common young adult (YA) literature elements in Rot & Ruin. Benny is facing the challenges of growing up and finding his place in the world. He has changing ideas about his family. He is in a complicated romantic situation(because really, what romantic situation at age 15 isn’t complicated?). All of these things together make the book relevant for young adults, while other common motifs in current YA literature – zombies, apocalyptic events, action/adventure – provide an accessible format.

The book opens with a crisis: Benny must find a job or lose some of his food rations. While most young adults today can’t imagine such a perilous position, Benny’s reaction to the jobs he tries out is a common feeling for young adults: boredom. Beginning the novel this way lets Maberry show that, while Benny isn’t necessarily in a situation that young adults can relate to, at least Benny himself is relatable.

And Benny’s relationship with Tom is also relatable; while Tom is Benny’s brother, and there is clearly some brotherly tension in their relationship, Tom also functions as Benny’s parent, and Benny fights against his authority like most young adults rebel in some way against their parents. In Tom, young adults can see both siblings and parents, and through Tom, young adults may begin to see that, while parents may come across as obstinate and strict, there are often reason guiding their words and actions. My biggest (well, only, really) problem with the novel is actually that Benny is so hesitant to change his opinion of Tom. Even when he sees proof that the zombies are not the evil beings he believed, he doesn’t completely change his opinion of his brother; he even still speaks of hating him. It is not until he believes his brother to be dead that a full change is complete. Maybe it is because I have more than a decade on Benny and now identify more with Tom, but this change in Benny was too slow for me.

Benny’s complicated romantic situation involves his childhood friend, Nix, and a girl whom he has never met, Lilah. Benny is determined not to like Nix, as he feels that this would complicate their relationship, and his friendships with their other close friends. These are common young adult situations; as children grow into young adults, they begin to look at the other gender (and in some cases, those of the same gender) in different ways. Suddenly, they aren’t just playmates – they’re potential partners. And Lilah is Benny’s version of a celebrity – and we all know how young men are with celebrity women.

Through all these common young-adult situations, Maberry creates a powerful tale that most young readers should be able to relate to on some level. Rot & Ruin (ISBN 978-1-4424-0233-1) was published by Simon & Schuster in 2010, and is available through their website for $17.99. It can also be found through most other common booksellers.

_Feed_ Response: my rant against people who think our language is failing

Posted: November 27, 2011 Filed under: Bookhenge 1 CommentIn Feed, Anderson throws you into a dystopian American – where cars fly, everyone lives under a dome, and steak is grown in a field (and not on a cow). Titus narrates the novel, and this world is normal to him, so it takes a while to realize that things are not alright. People are getting skin lesions. There is political unrest aimed towards America. Nothing can live in the oceans anymore. And then there is the Feed. All Americans who can afford it have a computer chip implanted in their brains at birth; not only does this feed take over control of bodily functions, but it also has begun to take the place of communication, entertainment and advertising. People with the feed can watch shows, chat with each other and play back automatically recorded memories, all inside their heads.

I have to admit, through the entire first half of the novel, I was annoyed. I was annoyed with Titus, who is self-centered and immature, but more than that, I was annoyed with all the characters’ use of language – all the characters struggle to speak, and when they do, they do so only in fragments, laden with slang and profanity and pauses and “like”s. But it wasn’t that the language was bad that annoyed me – actually, I was annoyed with the author, M.T. Anderson. He seemed to be writing the novel based on the assumption that language decays over time, if we let it. In fact, one of the characters is quoted as saying this: Violet (she’s the love interest of Titus, and the main source of conflict in the book) says her father thinks the language is “being debased” and “is dying” (Anderson, 2002:137).

The thing is, this isn’t how language works. Language is as innate in humans as blinking or breathing. It’s a natural process, and it doesn’t need protected or guarded or taught. It changes and adapts to new situations (in fact, every language is always changing). Dialects – and everyone speaks one – are varieties of language. All dialects are governed by rules; rules that are ingrained in us and are logical and complete. Everyone speaks a dialect, and everyone’s dialect works just like it’s supposed to.

This isn’t just a liberal hippie rant. It’s supported by facts, by evidence.

I can prove it.

I will show you a well-known language feature from some rural American dialects, one commonly mocked and considered “bad English.” And I will show you that it is governed by very specific rules, some of which we know are rooted in the history of the language.

A-Prefixing[1]

In several American dialects, most of which are located in the Appalachian Mountains, there is a dialect feature called a-prefixing, as in He went a-hunting yesterday. While the feature is fading (as speakers who have it are getting older, and it hasn’t been passed to younger generations), it is still a commonly recognized (and stereotyped) feature.

While this dialect feature is often ridiculed as “bad” or “stupid” English, in fact, it follows three specific grammatical rules. Unless all these criteria are met, the a-prefix doesn’t appear. What’s cool about this feature is that it seems to have roots in all English varieties, and as such, it is easy for native English speakers to recognize when the a-prefix should be applied and when it should not. This makes it an ideal activity for showing that all features of all dialects have rules, even ones we consider bad or wrong.

I’m going to give three lists. For each number, only one of the a-prefixed words are correct. Read them aloud and decide which of each sentence pairs sounds better. When you are done, highlight the line that says “ANSWERS”, and you will see the correct answers. After each list, I’ll explain the rule.

LIST A: Sentence Pairs for a- Prefixing

- a. A-building is hard work

b. She was a-building a house - a. He kept a-running to the store

b. The store was a-shocking - a. They thought a-fishing was easy

b. They were a-fishing this morning

Answers: 1)B 2)A 3)B

Did you get them right? Can you tell what the rule is? If not, think about parts of speech. For each of the correct answers, the a-prefix attaches to a verb.

LIST B

- a. They make money by a-building houses

b. They make money a-building houses - a. People destroy the beauty of the mountains through a-littering

b. People destroy the beauty of the mountains a-littering - a. People can’t make enough money a-fishing

b. People can’t make enough money from a-fishing

Answers: 1)B 2)B 3)A

How did you do this time? Can you name the rule? Again, this has to do with parts of speech. The a-prefix cannot attach next to a preposition. For this rule, we actually know the reason why: at some point in its past, the a-prefix functioned as a preposition, and in English, you can’t have two prepositions next to each other.

LIST C

- a. She was a-discovering a trail

b. She was a-following a trail - a. She was a-repeating the chant

b. She was a-hollering the chant - a. They were a-figuring the change

b. They were a-forgetting the change

Answers: 1)B 2)A 3)A

This one is the toughest. Did you get it? It has to do with syllables: the a-prefix only attaches to words that have the stress on the first syllable.

So there are three rules for a-prefixing, all of which are embedded deep in the grammar of speakers who have this feature. While many consider this to be wrong or bad English, it is actually perfectly grammatical.

Which brings me to this: all language is grammatical. While prescriptivist grammarians may claim that we need to govern language rules and keep a close eye on our language, lest it decline into incomprehensible babble, that’s simply not how language works. It will go on, complete and full and grammatical, whether or not we prescribe rules and monitor our speech. Anderson’s admonitions, given through the disjointed speech of his characters, are unfounded, and really, knowing that lessens the blows of the other, more solid critiques on our culture.

Works Cited

Anderson, M.T. (2002). Feed. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

1 This exercise taken and adapted from the dialect curriculum create by Jeff Reaser and Walt Wolfram of the North Carolina Language and Life Project, here at North Carolina State University’s linguistics program. I had the privilege of working with the NCLLP and both Jeff and Walt as an MA student here at State, and I taught this curriculum at several elementary and middle schools across the state.

BACK TO POST

Multicultural Literature

Posted: November 10, 2011 Filed under: Bookhenge, Uncategorized 5 CommentsBefore the readings

I am going to begin by talking mainly about African American literature, only because I have a good example and good resource for doing so. I don’t actually have much experience with the pedagogy surrounding multicultural literature, so this is really the best way for me to access the topic. I understand that the topic of multiculturalism is much broader than just African American literature, and that the topic at hand is awards, not curricula, but this was how I began to think about the topic.

My good friend Sara (you may remember her from here) is getting her PhD in African American literature from University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Before Sara, I have to admit that I never thought about the pedagogical and systemic justification for teaching African American literature (or any minority literature) separately from the rest of the canon.

It is an interesting situation. Teaching African American literature separate from the canon implies that that literature progresses separately from all other literature – so the themes, issues and societal things that influence other (presumably white) literature does not influence African American literature, which simply is not true. And yet, there are special issues brought up by African American literature. And this literature has long been left out of the traditional canon, so teaching classes dedicated only to African American lit is a way to begin to right that wrong. As Sara explained to me, the latest trend in teaching African American literature is to make sure to situate the literature being taught into the broader trends that were going on in the other literature being written at the time. Until African American literature has equal recognition in the canon (and I won’t even try to define the canon), this seems to be the best solution. Though one could make the argument that continuing to teach courses dedicated to African American literature makes it harder to include such literature in more general survey courses.

Whew. This is complicated.

After the readings

I was almost equally swayed by both Aronson’s and Pinkney’s arguments, which makes sense, given my non-stance on teaching African American literature in a separate course. Aronson’s most compelling argument for me was that integration is the only acceptable way to recognize any literature. It made sense – like integrating African American literature into standard survey courses. I underlined the sentence “Creating a new award is a concession that the other awards will never change” several times (2003:6). I also liked his argument that we should focus on content, not biography.

But Pinkney’s argument (and the arguments of other Aronson opponents that he discusses in Chapter 3) that we don’t live in a perfect world, and full integration has not happened, thus awards for multicultural literature are still necessary, was equally persuasive for me. When I read this, I realized that Aronson’s argument for integrated awards might be too idealistic, however logical it sounds.

Both sides make good points, and ultimately, at this point in time, I don’t think there is a right answer. What is the best approach, then, is open, honest discussion – much like what Aronson and his colleagues do in Section 1 of Beyond the Pale. Hopefully someday Aronson’s idealized vision can happen. Until then, the awards that the ALA gives out will serve as a guide for those looking for diverse and enriching literature.

As for how to expand young adults’ exposure to multicultural literature, I think the biggest first step is making sure including different cultures’ voices is a classroom priority. An ALA Best Books for Teens multicultural list would be helpful, but teacher awareness seems to me to be far and away more important.

Works Cited

Aronson, M. (2003). “Slippery slopes and proliferating prize.” Beyond the Pale: New essays for a new era (3-10). Maryland & Oxford: The Scarecrow Press.

On interconnectivity (and my compartmentalization tendencies)

Posted: November 4, 2011 Filed under: Bookhenge 4 CommentsI first started keeping a personal blog a little more than a year ago. Well, it’s not a personal blog, really, more of a family blog. Both my family and my husband’s family live out of state, and when we got married and bought a house here in Raleigh, we wanted our families to be able to keep up with what was going on. So I started a blog, mainly to share house decorating changes.

I was surprised when I started how different writing for a blog was than any other writing I had done before. To be honest, it took a while to get used to! At that point, I already had a pretty substantial collection of blogs I read regularly … and, you know, I teach writing for a living … so it took me a while to figure out why I was so stymied.

When I was little, I never liked to mix my toys (this is related, I promise!). My Little Mermaid figures could never play with my stuffed animals; Strawberry Shortcake never had Rainbow Brite over for a tea party. In my head, they were from different worlds – different dimensions, even – and they couldn’t mix. Call me a toy bigot. But in my head, it just didn’t work.

My compartmentalization continued into my school years. I had to have a separate folder for each subject; by the time I got to high school, I was carrying around eight different binders. When I got my first computer in college, one of the first things I did was create and label folders for each of my classes, and embed them in folders labeled for each semester. And there was a complete separation of personal and professional; I had two email accounts, and at that point, I was working, and so I divided my closet in two: clothes I wore to work and other clothes. I even had a separate pair of shoes I only wore to work.

I could go on and on with examples. It must be genetic, because my brother is worse than I am. It’s so ingrained that I didn’t realize until months of blogging that that was why I didn’t like the format: everything is so interconnected. Pictures go with texts, links can go outside my own website, the text is out there and public to be read – even to be found by my coworkers or students. Yikes! It’s everything I have avoided for my whole life!

Once I realized my block, though, I actively worked to adapt. I always teach my students that they need to mold their writing to the expectations of the discipline or genre. That is a part of writing. So I took my own advice and tried. Turns out, I love it! This is a good example of how far I’ve come. I created a diagram to show what I was explaining, I inserted a picture from an outside website (with attribution! I don’t know if it is fair use or not, but I know of quite a few professional bloggers who link from Pinterest, and I know that the Pinterest site tries to keep up with those things and take down the pictures that are copyrighted), and I link to two exterior sites (three if you count the link to the picture). I also use strikethrough text and all caps for effect, something that is new to blogger me.

A year ago, all of those exterior and visual elements would have bothered me. As would linking to my personal blog from my professional (err, student) one. Ok, so that one still bothers me a little, but I think that’s healthy. Some separation is healthy (I would never, say, friend my current students on Facebook). I can’t say I’m a savvy blogger (let’s face it, my personal blog only has 20 posts), but I think I’m getting used to the format.

All that to say (and I know I’ve said a lot!), reading about the Radical Change theory (Dresand, 2008)immediately scared me. Are these the types of texts I’m going to have to teach?! Eek! But after I took a step back, I realized how beneficial this would be for students. Having a text that is web-based, non-linear or interactive would not only engage students, it would broaden their technology boundaries.

An aside, and I think I’ve harped on this before – Though we assume today’s students are really tech savvy, that is not what I have found in my classes – students are comfortable with certain types of technology or tech-based communication (Facebook, Twitter, texting), that doesn’t necessarily translate to other types of technology (many of my students come into my classroom not knowing how to double-space a Word document or send a formally worded email to a professor).

And I think graphic novels are a great way to take a step towards more interactive texts while the technology is catching up with the theory (isn’t it usually the other way around? or is that how technology goes in the world of education?). I loved Trythall’s story about Hector, the student who had never been interested in English class until she gave him a graphic novel. If graphic novels get young adults reading – if it gets them engaged with the material – then they are absolutely useful in the classroom. Especially since graphic novels have come a long way from only superhero comics (though I think there is value in those too!); the Change Project‘s wiki entries for graphic novels with social justice components prove that.

I’ll end on this note (which I’ve ended on before; maybe it’s becoming my blog’s theme?): The book that serves your students the best is the one they should read.

Works Cited

Dresang, E. T. (2008). Radical change revisited: Dynamic digital age books for youth. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 8(3).

Trythall, A. Manuscript.

The Stepchild

Posted: October 21, 2011 Filed under: Bookhenge 3 CommentsNonfiction has always been my least favorite (step above) genre. It’s not just reading it, either; I started out as a creative writing concentration in my English major in undergrad (I was a bit misguided: I am certainly no creative writer, no matter how hard I want to be!), and even though it was in my nonfiction class that I met my future husband, that course was my least favorite creative writing class.

I always believed that I didn’t like nonfiction because I usually read as an escape; why would I want to read a “real” story when I could run off into a whole new world? But after reading Aronson (2003a)’s chapter on biographies, I realized why this might be: I have never read a good biography and not nearly enough good nonfiction more generally. The conflict between portraying the time and portraying life is a big one (and wouldn’t the conflict be the same for memoirs or autobiographies?), and I think this is what has kept me and, I would imagine, many, many others, from truly loving the (step above) genre.

But I don’t want to pass on my upturned nose to my future students, as I believe that nonfiction is a natural place for students to learn the connectedness of history. While biographies and memoirs can fall in to the fracturing-of-history trap that Aronson (2003b) talks about in his history chapter, I also think students are more likely to get a holistic view of a time better from creative nonfiction than from a history textbook. It’s also a natural link between disciplines; linking English and history classes at the middle- and high-school level could be as easy(ish) as giving a nonfiction reading in English that is tied to the period in history they are learning.

And while I’m not sure I buy Aronson (2003c)’s implied demasculinization of society–not knowing how to teach your son to fix a car doesn’t mean that you are less of a man–I do buy that there are different needs for boy readers (and girl readers too, though that’s not the focus here) than what is being published for them. Nonfiction seems a natural fit. Writing stories about men, and, if we are to buy Aronson’s physical argument, perhaps men who have achieved physical mastery in some way, would both stand in for the dads who can “no longer [fix a car]” (102) as well as give boys something to read that they actually want to read about.

Speaking of actually wanting to read, the very reason that nonfiction has become the neglected stepchild of YA literature (Aronson, 2003d)–because it is hard to write, because there is so much at stake–is the very reason we should strive to include it in our classrooms. These types of books give the challenging, human (and, as I said above, hopefully holistic) look at history in a way that our texts and classes right now are now. The pendulum has swung too far away from a strong, complete (and honest) view of history, and nonfiction would be a good way to get back on track.

Works Cited

Aronson, M. (2003a). “Biography and its perils.” Beyond the Pale: New essays for a new era (69-72). Maryland & Oxford: The Scarecrow Press.

–. (2003b). “The pursuit of happiness: Does American history matter?” Beyond the Pale: New essays for a new era (75-83). Maryland & Oxford: The Scarecrow Press.

–. (2003c). “Why adults can’t read boy readers.” Beyond the Pale: New essays for a new era (99-103). Maryland & Oxford: The Scarecrow Press.

–. (2003d). “‘Woke up, got out of bed, dragged a comb across my head’: Is the past knowable?” Beyond the Pale: New essays for a new era (105-115). Maryland & Oxford: The Scarecrow Press.

Literature Review Lite + ALP Proposal

Posted: October 12, 2011 Filed under: ALP, Bookhenge Leave a commentIntroduction

Surprisingly, at least to me, there is not a lot of empirical evidence that supports the now-ubiquitous common-reading programs for first-year college students. It’s surprising to me for two reasons: one, I like to think that most curricula decisions made by universities are well researched and purposeful (idealistic, I know). Two, academics will research anything that moves within the university, given the easy access to data, so the common reading program seems like a prime candidate that is ripe with new research possibilities. Perhaps the common reading programs are still too new, and research hasn’t caught up with the trend. In any case, it seems I am stepping into new territory.

That’s not to say there is no material on the subject, and I hope to use that, combined with North Carolina State University’s information about our own Common Reading Program (CRP), to explore how CRPs are designed, and whether or not NCSU’s program is meeting its goals.

My assumption going in is that sadly, NCSU’s program is falling short of its potential. Every semester, I have students come into my English 101 classroom assuming that we will be working with their common reading for the year, and when I inform them that we won’t and ask them what other ways the text is used, often I get blank stares. It seems that the reading has not been well integrated into their first-year experience. This is definitely seems like a missed opportunity, and I look forward to exploring other options for integrating it here at NCSU.

Goals of CRPs

Barefoot (2000) sees the common reading programs as an opportunity to undercut students’ expectations of a party-filled college career, and to get them focused early on academic pursuits. She claims that if the common reading experience is integrated into other orientation programs, the intellectual engagement will be more immediately associated with college. I would like to think that this view is a bit cynical; while I imagine that there are many students who do expect school to be more partying and less studying, I have seen enough first-year students who come to my class very obviously nervous about handling their course loads and eager to impress me (and their other professors) to think that a CRP’s goal should not be first and foremost to startle students into thinking about academics.

Gilbert and Fister (2011) have a more positive outlook on CRPs: “… reading in common programs straddle the book club orientation to reading as an opportunity to discuss a book informally with others in a social setting and the eat-your-vegetables imperative of an assigned reading” (476). This seems to be the purpose of NCSU’s CRP; according to the New Student Orientation web page, “The purpose of the NC State Common Reading initiative … is to create a common educational and interactive experience for incoming undergraduate students, introducing them to the University’s institutional and academic values and expectations, including engagement as members of this community of scholars” (“First-Year Students: Common Reading”). A “common educational and interactive experience” implies that there is some sort of common activity or assignment. The common experience is broken down quickly, however: “Each college has different expectations of their students regarding the Common Reading; some will have a related assignment, blog entry, or small group discussion opportunity during the semester.” So despite the name, the reading is very obviously not common to everyone. Simply browsing the different schools’ requirements shows that the College of Design, the College of Natural Resources and the College of Textiles do not require students to complete the common reading (and the College of Engineering doesn’t have a link; the directives state that each college’s info will be updated “as it is confirmed,” so clearly the CoE never got back to the committee).

That brief look at the CRP page, along with my interactions with my own students, tells me that the program here at NCSU isn’t meeting its goals. But before I make that judgment, I would like to know what activities are actually offered, and what role they play in the CRP.

Activities

There are two basic ways universities usually incorporate the common readings: either as an aspect of orientation or as a part of a larger program that spans the whole semester (Ferguson, 2006). The former type of CRP is more common, and that is what we do at NCSU. Other than to say that individual colleges will have their own assignments (including blogs, discussions and other assignments), nowhere on the various NCSU websites is a list of orientation activities related to this year’s common reading. On the NCSU Common Reading Selection Committee’s page, they say that “Ideally, the chosen reading will gain additional dimensions by connecting readers with the author as keynote speaker for the annual Wolfpack Welcome Week Convocation and start-of-academic-year activities across campus.” This is rather vague, and finding out what types of activities are offered is my first step in this project. I have an email out to a member of the Common Reading Selection Committee.

Alternatives & My Plan

When I first started doing research, I expected to find basic variations on a theme. For the most part, I did – CRPs that focus on orientation only and ones that last a whole semester are year are definitely the most common kind. But then I found a paper on the CRP at Buffalo State College. BSC has an interesting take on the CRP, and it is worth exploring and considering.

Instead of a text, students are given a multimedia CD (Sanger, Ramsey and Merberg, 2008). The first semester they tried it, in Fall 2004 semester, the theme “Think Big” was chosen, and monthly topics of discussion guided the choosing of activities. For each monthly theme, they included one spoken text, one written text, one visual work and one musical work. After 2004, the CD concept took off; they reused the 2004 CD for one more year, and then created one per year until at least the publication of their article. Its application also grew far beyond student orientation. The materials were used campus-wide each year. The faculty of BSC also indicated that the CD is easy to include in classroom activities, because of the diversity and breadth of material available. “Because most of the pieces included are brief and intellectually accessible, a discussion of one can be added to a broader class theme without major planning or rethinking of other course content” (8).

Implementing such a radical change to the CRP program here at NCSU would be difficult, not only because it would require and administrative change (red tape, anyone?), but also because NCSU is more than double the size of BSC. While I am still leaning towards suggesting this type of change, there are other options to explore. Ferguson (2006) gives an overview of the types of activities associated with CRP programs. The most common types are author talks and small-group discussions, but other activities include online forum discussions, student essay contests, required essays for introductory courses, library orientation activities and cultural events like films, performances and exhibits. These types of activities would be easier to implement in the current CRP program here (and, for all I know at this point, already are).

As I said above, my first step is to find out what kind of activities are associated with the common reading. The next step is to ask first-year students what their impressions of the CRP are. So far, these are the questions I know I want answered:

- When they first received the common reading book, what was their understanding of how it would be used? Did they think it was for class, for orientation activities or for something else? If they thought it was for a class, did they think it was for English 101 (which seems to be a common assumption)?

- What type of activities do they remember being offered during orientation that related to the common reading?

- Which (if any) of these activities did they have to attend, and which could they elect to? If the activities were optional, did they go?

- Has the common reading been incorporated into any of their classes this semester?

I’m sure as I learn more about the program, I will add a few questions to the list.

Finally, I want to make suggestions for how the CRP can be improved. Even if my assumption that the program isn’t successful as it is now, there is always room for improvement. The ultimate goal would be to have a program that better allows students to react to and interact with the material found in their common readings. Right now, I am leaning toward suggesting a program similar to BSC’s multimedia CD (and if I do, I would like to put together at least one small thematic unit to show how it would work), though I am keeping my mind open during the investigation stage.

What role the CRP actually plays in the first year of college for students at NCSU is something I have been curious about since my students asked me about it in my first semester of teaching here in 2008. I look forward to finally getting some answers!

Works cited

Barefoot, B. O. (2000). The first-year experience: Are we making it any better? About Campus, 4(6), 12-18.

Ferguson, M. (2006). Creating common ground: Common reading and the first year of college. Peer Review, 8(3), 8-10.

“First-year students: Common reading” NC State New Student Orientation. Retrieved from http://www.ncsu.edu/orientation/firstyear/commonreading.php.

Gilbert, J., Fister, B. (2011). Reading, risk, and reality: College students and reading for pleasure. College & Research Libraries, 72(5), 474-495.

Sanger, K. L., Ramsey, J. E., Merberg, E. M. (2008). The multimedia CD as a new approach to first-year reading programs. About Campus, 13(1), 7-9.

“University Common Reading Selection Committee.” North Carolina State University Undergraduate Academic Programs. Retrieved from http://www.ncsu.edu/uap/reading/index.html.

10/13 Update

While I plan on curating materials that fall outside even our broad definition of YA literature, I still plan to incorporate as much as possible. And when I studied our LTLWYA framework, I realized that the framework doesn’t actually limit us to teaching with YA lit; the elements are actually much more broad and could be good guiding principles for a multitude of subjects. In my case, I definitely plan on proposing the use of technology (I envision an interactive webpage with the materials I curate); I think this is an appropriate use of technology, and may even make the material more accessible than a book (that has a tendency to be left at home, on the bus, etc). I think having multiple options for each topic will also allow for a real-world connection (or at least a reading-to-classroom-then-to-real-world connection), and allow individual instructors to be creative in their inclusion of materials in the classroom. Having multiple genres will also allow for different types of access for students with different learning styles, which is a positive, according to the theory of multiple intelligences. Having more selections would even allow for more participatory learning; I could envision assignments where different groups of students were assigned different readings from the list, and were instructed to share them with the class in some way (bookcasts, perhaps?) As I said, our framework actually moves beyond just teaching YA literature with young adults, and I can’t wait to see how it applies to all aspects of my ALP.

Promise & Peril

Posted: September 22, 2011 Filed under: Bookhenge 9 CommentsIn the world of composition instruction, there have always been ongoing conversations about what our courses are supposed to accomplish. Is our job simply to teach writing? What does that mean? Do we teach the kinds of writing our students will encounter in the university? Or do we teach business writing, something that will be more useful to them later?

A question that is more applicable to me today, though, is the question of social responsibility; is our course an appropriate place to (try to) craft responsible citizens? There are many instructors who believe that the composition classroom is a good place to teach civic lessons along with writing.

Personally, I am of two minds when it comes to the civics/literalist divide in composition. Part of me believes that it is my job to teach students how to write; my current department values academic writing in the composition class, so I focus on the kinds of writing my students will have to do in college. But the other part sees the opportunity to teach other valuable lessons. My course is, quite literally, the only universal requirement for all students (as is the case in most universities), so why waste an opportunity to instill good citizenship in our students?

But really, who am I to have that responsibility? I consider myself a fairly good citizen: I vote in every major election, I contribute to good causes when I can, I recycle more than I throw away. But those are things that I consider a part of being good citizen. If people only did what I do, our government and way of life would grind to a halt. We would have no military, no Congress, no one to pick up my recycling. If people only believed in my version of civic mindedness (which NCSU students don’t; by and large, my students are quite conservative), I’ll be honest, taxes would be too high because there would be no one to argue with me about the importance of public services. While the two-party system is problematic, what would be more problematic would be a country full of me.

All this to say, even at the college level, where students are adults and already have their own ideas about how the world works and their place in it, we have conflicts about whether or not we should teach just the content, or use that content as a springboard for grander aspirations. When talking about the role of literature in the young adult classroom, the stakes are even higher. The students are not, of course, adults, and are in a lot of ways, they are more vulnerable and impressionable (and it is our job as teachers to make some of those impressions).

And teaching lessons through literature is a lot more indirect than telling my college students they should vote. Like Aronson (2004) explains, it’s impossible to know how any individual will respond to any piece of literature, let alone a group as diverse as “all young adults.” That’s not to say that I think teaching social justice through literature is impossible. But I think it has to be done purposefully and carefully, and that we as teachers should understand that not every student will come to the same conclusions about a work, and, more importantly, that that’s ok. Good, even. Each student can contribute to the conversation, and as I have learned so clearly from this class so far, it’s that often a symphony of voices that is valuable, not just the solos. Through collaborative learning, students can essentially teach themselves the life lessons we want them to reap from literature.

This, of course, assumes the moralist argument, not the literalist one. But of what use is literalist teaching of literature? Is it really helpful for students? I’m not sure I see the point in teaching metaphor and allusion and Shakespeare’s sonnets to a bunch of disinterested youngsters (future English majors, sure. Let them take electives on literary analysis). Where is the benefit? I don’t know if the “to make them more well rounded” liberal-arts-education argument flies if you can’t articulate how it rounds them.

So I think I tend to fall on the moralist side, or, as Aronson (2003) calls it, in the “morals, role models, life choices crowd” (94). Given that, I think YA literature is a perfect fit in a classroom that is designed for collaborative meaning-making, since defining and reinforcing the traditional high-literature canon isn’t at the top of the to-do list. YA literature is generally more concerned with message than excellent prose (though the best examples of course have both).

Even if I agree that YA lit deserves a place in the young adult classroom because it teaches good morals – and, with the above reservations excepted, I do – what then exactly is a YA novel? As Aronson (2003) points out, a range of materials can reach teenagers, from books written for children through adult novels, and that our goal should be to expose them to as wide a range of experiences in art and literature as possible. And I think that is actually a good way to look at YA lit more specifically: as a range. While, as Roxburgh (2004) says, it is the only genre we define by the audience, I don’t know that it’s possible to always point to where YA lit ends and adult lit begins (much like it is hard to point to a moment where a young adult becomes an adult). But, aside from the issue of where to shelve them in libraries and bookstores, I’m not sure that’s really a problem. While we should be concerned with matching the text’s difficulty with our students’ reading level(s) (and that’s a problem I can’t begin to wrap my head around right now), I don’t know that we should limit ourselves – or our students – to just YA lit or adult lit. The book that serves your students the best is the one they should read.

Works Cited

Aronson, M. (2003). “What is a YA book, anyway?” Beyond the Pale: New essays for a new era (93-96). Maryland & Oxford: The Scarecrow Press.

Aronson, M. (2004). “How are children affected by the books in their lives? (Children’s literature).” World Literature Today, 78(2), 14(3).

Roxburgh, S. (2004). “The art of the young adult novel.” The ALAN Review, 32(2), 4-10.